“I’m going to get bad grades and then I can’t ever have screens!” my eleven-year-old yells, tears coming to his eyes. I could see Sebastian was already far up his mental ladder.

“Hold on! Hold on! Don’t get upset yet.” I interject. I was trying to stop him from climbing any higher. “How bad would your grades need to be to lose screens?”

Sebastian pauses, eyes wide.

“C’s or below,” my partner Travis chimes in.

“And what are your grades right now?” I ask, taking him down a rung.

“I don’t know.”

“Okay, so that’s something you need to ask your teacher about.”I can see he’s calming down and taking a few steps back down his ladder. “And if you do get C’s, how long will you not get screens?”

“Forever?”

“Until you get good grades again, which is a minimum of 9 weeks when the new grades come out,” Travis says.

“See. It’s not as bad as you thought. You’ve got some work to do, but remember before you get too upset make sure you have all the information,” I reassure him.

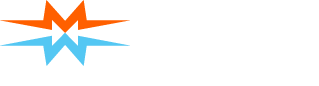

We all go up our ladders sometimes. The ladder I’m talking about is The Ladder of Inference, a psychological model created by Harvard professor Chris Argyris in 1970 and later featured by Peter Senge in his popular book “The Fifth Discipline” in 1990. It describes how we go from data and observations to conclusions and actions and all the messy steps in between. It can help you understand others’ decisions better and help you be skeptical about your own thinking. My favorite version of this model, pictured below, comes from Sheril Mathews of Leading Sapiens:

Basically, everything starts at the bottom of the chart with reality and all observable information. Of course that is way too much information for our brains to handle, so we have to select relevant data to understand what’s going on. That leads us to develop a story in our heads about what is happening and why, how we feel, and what we should do about it. Although this is an essential part of thinking, it can easily go wrong when you are missing data, selecting the wrong data, or making incorrect assumptions or conclusions.

In the example of my son freaking out about the threat of losing screens–a code red level 10 emergency that must be thwarted at all costs–I could see him going up his ladder. So I’m guessing his thought process was something like this:

1) Observable reality: My teacher gave me an assignment.

2) Data I Select: I have an assignment that feels overwhelming and impossible.

3) Meanings I Create: I can’t do this assignment or any of my assignments.

4) Assumptions I Make: I’m going to fail my class.

5) Conclusions I Reach: I’ll never get to have screens again and there’s nothing I can do about it.

6) Beliefs I Build: My teachers and parents are cruel and here to take away the best thing in my life: screen time.

7) Actions I Take: I can’t win. I should do the minimal effort on this assignment, finish quickly, and get in as much screen time as possible now before grades come out.

I try to disrupt this thinking pattern and teach him to ask himself questions about his own decisions and data to make sure he’s reacting effectively. As I watch him catastrophize and go from zero to sixty in a heartbeat, I’m hoping it’s a useful tool.

Once you catch yourself going up your ladder, Richard Ross, in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook offers three options you can try to drive yourself back down:

Reflection: Take a skeptical look at your thinking and see if you’ve gone up your ladder too quickly or made wrong assumptions or conclusions. Are there other ways of thinking about this? A different story to tell? Remember Hanlon’s Razor: “Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.”

Advocacy: Make sure others understand your thinking and how you arrived at your decisions and actions. This gives you an opportunity to check your work aloud and get feedback.

Inquiry: Ask questions to gather more data or understand someone’s reasoning. Don’t just go fishing to get confirmation. Ask open ended questions where the answers might surprise you.

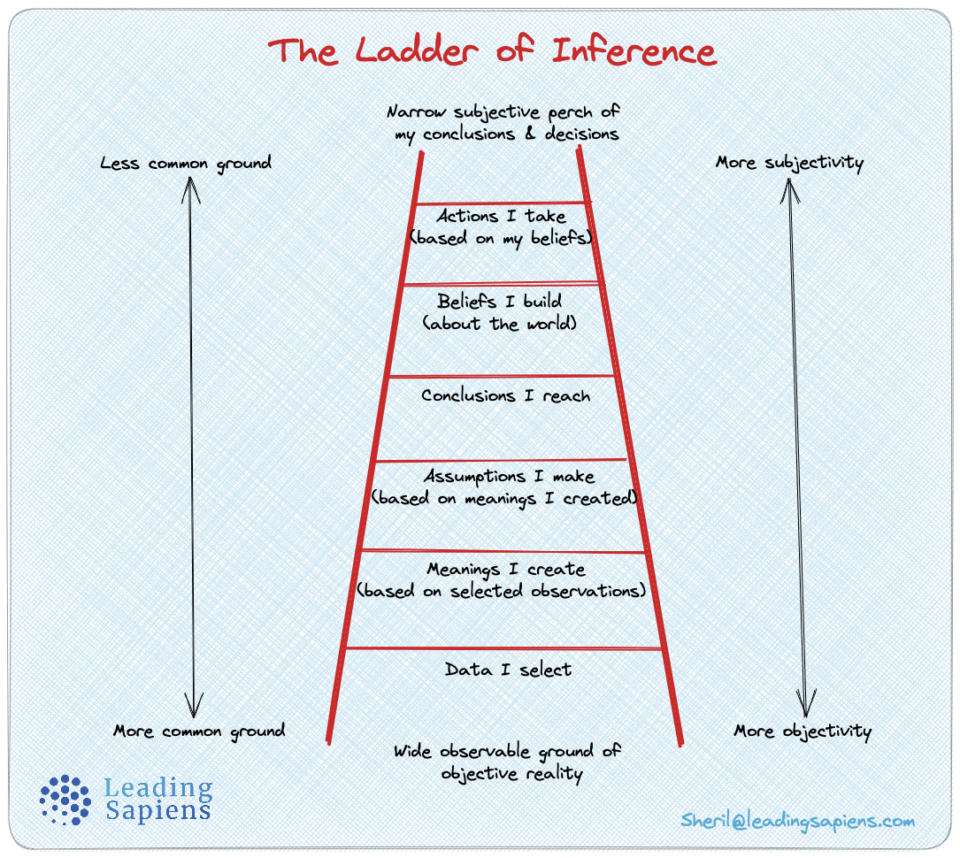

The Ladder of Inference also explains how smart, capable people might come to very different conclusions looking at the same data or observing the same thing. Part of that is because the ladder is cyclical, and your beliefs, conclusions, and actions change your reality and inform how you select data the next time.

With some practice you can start to see when you’ve gone up your ladder or where someone else did. This helped me earlier this year when a Facebook post in an improv group led me to discover someone had created a software system for managing an improv business–something I didn’t know existed and suddenly desperately needed. I checked out their website, set up a sales Zoom and invited the Dean of Merlin Works, Paul Normandin, to join me. And oh what a call! I was thrilled! I was sold! This was the answer we needed! And it’s the only one made just for companies like us. Plus they have a cohort starting next month! Let’s do it! Come on Paul, I’m up here at the top of my ladder and this is gonna be great, I know it!

But Paul, who has probably been on more software sales calls than I have, helped me slow down and go back down my ladder. He pointed out that we should really think through what our business needs were first and make sure this was really solving our problems. That the software might not be able to deliver on everything they promised in the meeting. And we should probably involve Karina, our registrar who would be using the software every day.

Oh… Right. I needed to take a closer look at my thinking and regroup. So what was a slam dunk in February turned into a much more methodical months-long series of software sales meetings and, of course, spreadsheets. It wasn’t until we’d already previewed five different systems that we finally found the software we really needed.

Although we’ve still got some kinks to work out, we are excited to share our new class registration, show ticket sales, and email and text communication system powered by Activity Messenger. Plus we are free from the claws of Paypal and enjoying the warm embrace of Stripe credit card processing. The Activity Messenger onboarding crew in Montreal have been so supportive and we’re hoping that signing up for things at Merlin Works is easier, that messaging with us is easier, and our staff can spend less time cutting and pasting and more time teaching and playing.

This is our first session using the new program, so please give us feedback–let us know what works, what doesn’t, and keep driving us back down our ladders.